FATHER LOVE

My father wasn’t an easy father for me to be a son to. I know I'm not unique, as a son. I think many (all?) of our fathers want things for us and from us. Sometimes that casts a shadow. Sometimes it's an inspiration.

Apprenticeship to Love: August 21, 2025

- Today’s question: How old were you when you began to appreciate your father?

- Today's practice: A father love practice (see below)

Rev. Hans Peter Meyer

TODAY’S MEDITATION

Today is my father's birthday.

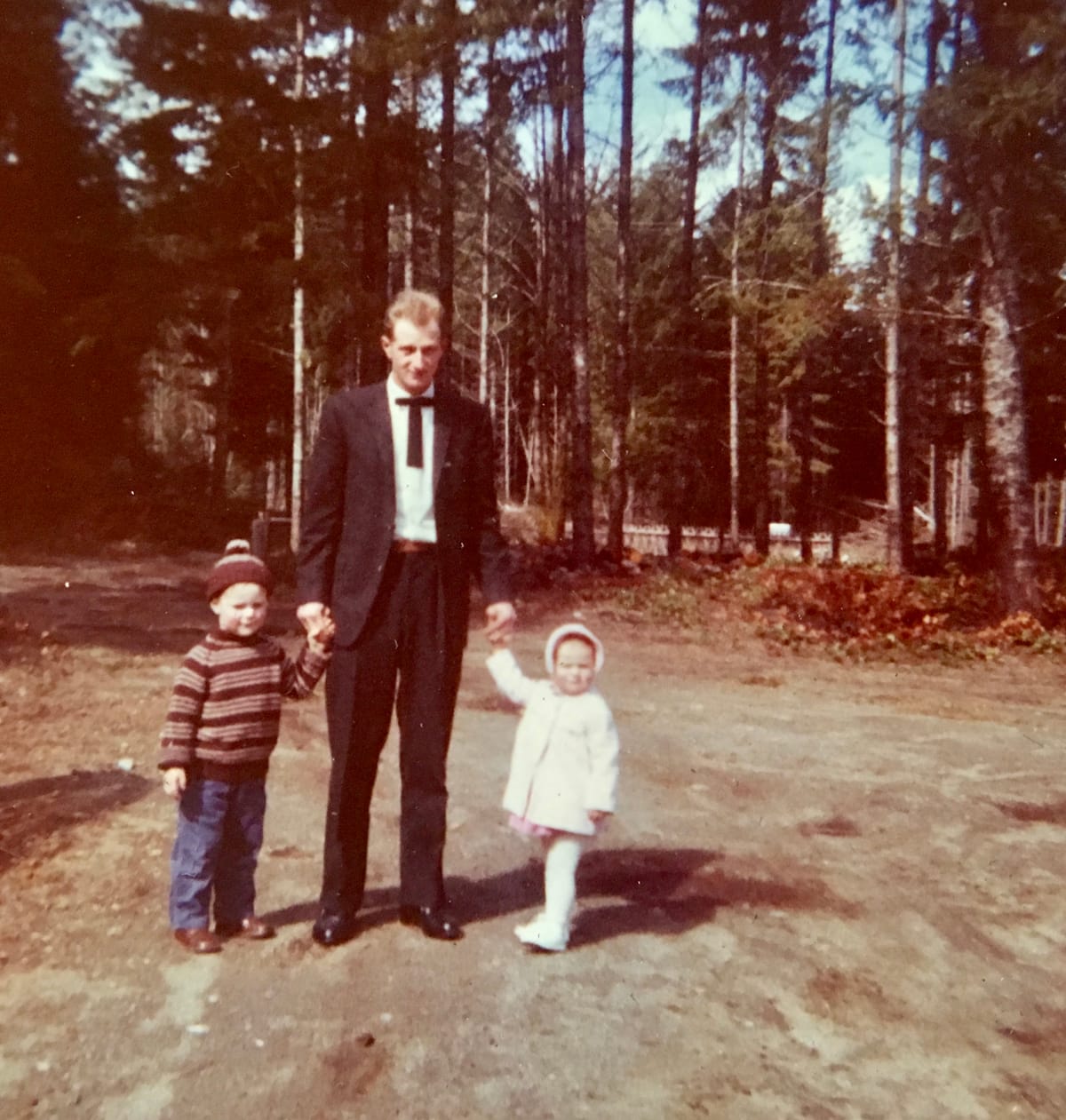

The picture at the top of this chapter was taken in early spring or late winter in the early 1960s. I am standing with my father and my sister. Our forested front yard is behind us. We're looking towards my mother. She is standing in front of our house, a house my father built, pretty much on his own, at 21 years of age.

Judging by how my father (I loved those ties!) and sister are dressed, and by the polish of my shoes, it was a Sunday morning. We were on our way to church. My mother would have snapped the pic just before we piled into the four-door hardtop ‘55 Oldsmobile my father adored. It was brown and white. Just like the sweater and toque I'm wearing, newly knit by my mother (I would lose that toque one day while sitting in the open window of the car as we sped up Miracle Beach Rd. —No seatbelts! Kids hanging out of cars! Those were the days...).

We were on our way to worship and sing at the United Mennonite Church (one of two local Mennonite churches, because even the smallest Mennonite community experiences a schism, sooner or later...). My grandparents helped found this church in the 1930s, in Black Creek, on Vancouver Island. This was the endpoint to a decade or more of wandering. From Russia, then Siberia, the civil war, a voyage to and attempt at settlement in Mexico, then Manitoba, and finally, a settlement that took. In the new promised land, Black Creek.

My father is about 25 in the photography. His wanderings had led him, aged 18 in 1956, from post-war northern Germany. He joined two of his brothers. The brothers were living in a small shack in Black Creek (my father referred to their living standard as akin to living in a pig-sty; he moved out shortly after arriving). By the mid-1950s the settlement had established itself as a German-speaking Mennonite agricultural village. Soon he joined his brothers, like most of the Mennonite men, working for Elk River Timber. It was one of the larger logging outfits in the region. Later I too worked for ERT, briefly.

...

My father wasn’t an easy father for me to be a son to. I know I'm not unique, as a son. I think many (all?) of our fathers want things for us and from us. Sometimes that casts a shadow. Sometimes it's an inspiration.

A few of the things my father wanted of me: that I would enjoy fishing (I did not); that I would pick up his talent for handwork and home improvement (I did not); that I would NOT become a logger (I did, but only briefly); that I would learn to be play music and sing (I did learn to play various instruments, and later, as an adult, sang in choirs); that I would love to dance (for many years, in my 40s and into my 60s, I enjoyed social dancing, with tango as my preference).

I'm pretty sure I disappointed my father's notion of who I could be a son, certainly in my childhood and teenage years, and even into my early adult years. I certainly knew, before my teens, that he was a disappointment to me as a father. Nevertheless, I always knew this too: that he loved me. I didn't know how much I loved him until much later.

...

Is father love like other loves? As a father, and as my love deepens, is there less claim to possession or expectation? Is there more freedom for me to simply experience and enjoy what is offered?

As his son I experienced this willingness to allow my father to be free to be who he was. Eventually I stopped expecting him to be the father I wanted him to be.

This happened the year I turned 40. It was a year of many changes. This was a beautiful change: Finally, I let my father be the man, and father, he was. Finally, I let myself appreciate him.

My willingness to let him be as he was allowed me to have about 20 good years with him. A long honeymoon, together.

...

Thank god for the wisdom that —sometimes— comes with getting a little older. It wasn't just age, of course; it was the coming together of many disappointments, leading me to understand how much I was standing in my own way of the love, and the beauty, and the joy that was right here.

Father love is a strange thing to think about in this context. As a son, I first felt my father's love as adoration. My sister was his favourite, there was never any question of that. But his favour was not at any cost to the love he felt for me, nor the promise he saw in me. He believed in me. Even though he didn't understand so much of what was important to me, as a child or as a man, he believed in me. Was proud of me. Loved me. I always felt that.

...

I have been a father for almost 40 years. I am, in a few weeks, five years a grandfather. This gives me another appreciation of how this man was my father. Some of the things that seemed odd now make sense. Or are less odd, especially as I find myself becoming my father.

...

A friend, talking about his father, told me that he only had short moments where it felt as if he and his father had any mutual acceptance of each other. "He was always pretty guarded," he added.

Is that our fathers' gift to us, as sons? That we become aware of how protecting themselves with hardness (because the world was hard for them, because their fathers were hard?) made our fathers less accessible to us, their sons?

Our work, as sons, is to find a way to stand on these troubled shoulders rather than blaming them for being hard and unwilling. I believe we have the opportunity, because of our awareness, to ask ourselves, How can I learn to be less protected, so that I am (paradoxically perhaps?) better able to prepare and protect my children, my wife, my family for this life?

...

Today is my father's birthday. He would have been almost 90 years old. His greatest gift to me was to let me know that he loved me, even when he did not understand me. I pray that my children and stepchildren feel this too. I pray that they know that their father and stepfather loves them, even —and especially— when I do not understand them.

★ If you have thoughts about "father love," please join me on the Signal Apprenticeship to Love chat group at https://signal.group/#CjQKIPbfC01rTfBN7f8peArlP_VtY3q8aK2uchw4kmlTLlZCEhDKe0nFRfMoRDapdf3hAB7V

TODAY’S INSPIRATIONS

🌀Thy right is to work only, but never to its fruits; let not the fruit-of-action be thy motive, nor let thy attachment be to inaction. (Bhagavad Gita, 2:47)

🌀You must take the next step (that is why your leg hurts). (My beloved, my Oracle and my Siren, my Muse)

TODAY'S SUGGESTED PRACTICE

Father relationships are sometimes difficult. Your practice, if you choose it and if you are able, and if your father is living: reach out. Call. Without expectation. Let him know you are thinking of him. If you are able to add a word or two of appreciation, offer that. Without expectation. Our right, as the Bhagavad Gita says, is to the work only, never to its fruits. If we have a living father, our work is to find a way to receive whatever father love he has been able to offer. If your father is not living, or if you are not ready and willing and able to talk to him, consider writing a short note to him. It may contain a list of complaints, or appreciations. It does not matter. Write it. And then, burn it. Allow whatever was written to become, like the smoke of the paper, something that is free.

PS. ARE YOU AN "EARLY READER?"

Some of you who receive today's chapter are already on the "1000 early readers list" for my book, Apprenticeship to Love. If you're not already signed up, and you'd like to receive regular chapters (1-3 per week as I get close to finishing the book), please click on the "subscribe" button at apprenticeshiptolove.com